In 1692, the small Puritan town of Salem, Massachusetts became the site of one of the most infamous events in American history. The Salem Witch Trials, a period marked by fear, superstition, and mass hysteria, resulted in the accusations of over 200 people, the execution of 20, and the unraveling of a tightly-knit community.

The trials, fueled by religious fervor and fear of the unknown, gripped the town and sent shockwaves through colonial New England. What began as a series of strange, unexplained behaviors in a group of young girls quickly escalated into a widespread witch hunt.

“The Salem Witch Trials were driven by fear and misunderstanding,” said historian John Demos, author of Entertaining Satan. “The combination of religious extremism and social tensions created a perfect storm.”

Witchcraft, or the practice of invoking evil spirits, was a deeply feared concept in Puritan New England. The Puritans believed that the devil was actively working to corrupt their society, and this belief contributed to their readiness to accuse their neighbors. Many of those accused were women, particularly those who didn’t fit into societal norms, making the trials a reflection of the era’s gender and social dynamics.

“It was a time of uncertainty, and when people are uncertain, they often look for someone to blame,” said historian Stacy Schiff, author of “The Witches: Salem, 1692.” “The trials allowed people to vent their frustrations, but at the cost of innocent lives.”

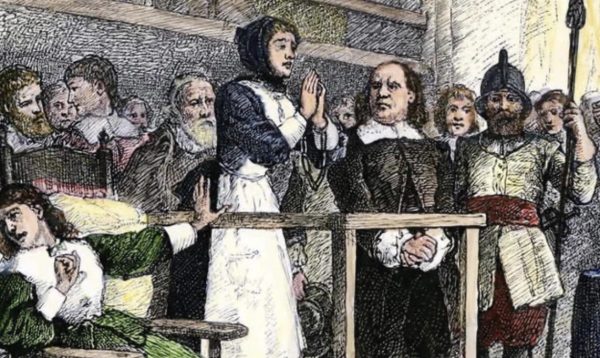

The first accusations began in early 1692 when a group of girls claimed to be possessed by the devil and accused several local women of witchcraft. These women, including Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba, were among the first to be arrested and brought to trial. Their trials, along with others that followed, were marked by a lack of evidence and reliance on “spectral evidence” — testimony that the accused’s spirit or specter had appeared in dreams or visions.

The most notorious case was that of Bridget Bishop, a tavern owner who was the first to be executed. Her supposed guilt was determined based on little more than rumors and accusations. Despite her protests of innocence, she was hanged in June 1692. Her death set the stage for a summer of relentless trials and executions.

As the hysteria grew, so did the number of accused. Neighbors turned on neighbors, friends on friends, in a desperate attempt to save themselves from suspicion. Those who confessed to witchcraft were often spared, while those who maintained their innocence faced execution.

“The trials showed how quickly fear can lead to injustice,” said Schiff. “Once the accusations started, it became almost impossible to stop.”

By the fall of 1692, public opinion began to shift. Many began to question the legitimacy of the trials, especially as more respected members of the community were accused. Governor William Phips eventually intervened, halting the trials and declaring that spectral evidence could no longer be used. In January 1693, the remaining accused were pardoned, and the trials came to an end.

In the years that followed, many of those involved in the trials publicly expressed regret. The Massachusetts colony eventually passed legislation declaring the trials a grave injustice, and in 1711, the government offered restitution to the families of those wrongly accused.

The Salem Witch Trials remain a powerful cautionary tale about the dangers of mass hysteria, scapegoating, and the breakdown of due process. More than 300 years later, the legacy of Salem continues to be felt, as the events have been immortalized in literature, film, and popular culture.

“The Salem Witch Trials remind us of the importance of reason and justice,” Demos said. “They show us what happens when fear takes over, and the cost of that is often far too high.”